How can I go faster?

Having come back to the time trial scene at the start of last year, after a break of ‘n’, years, I faced two challenges:

- How do I time trial fast enough to go under the hour on a 25 course, and under 24 minutes on a 10 – which is what I need to do to make sure I do go under the hour on a 25(!), and

- How do I TT and keep my blood sugar levels stable during the course of the event (being an insulin dependent diabetic gives this extra challenge!!). I may write about this one as I continue to experiment with my approach to time trialling this year.

One of my ‘classic’ mistakes last year (and always as far as I can remember) is to go out of the gate far too fast, against the advice of most. In theory, this is a simple bit of discipline to exercise, start fast (but not too fast), go faster. The theory, is much harder to put into practice, as it seems to go against your mental need to get going as soon as you are counted down to zero! I decided therefore to study the reasons why a little more, and I’ll be further trying to discipline myself this year to do just that. Even harder, is to determine how hard to go, and I therefore found some articles which seem to talk some sense about the way to go about it. An interesting article is pasted below, written by endurance athlete coach Joe Friel.

Time Trial Pacing

Joe Friel

What you don’t want to have happen in a time trial is to slow down gradually over the course of the event, “give up” and finish with a whimper. Yet this all too often happens. I’m afraid most athletes have too little patience and also believe that some how going our extra fast will lead to a better time than finishing fast. The problem is that when going out overly fast you create a lot of acid build up which causes you to slow at a greater rate than would have been the case had you been more conservative early on.

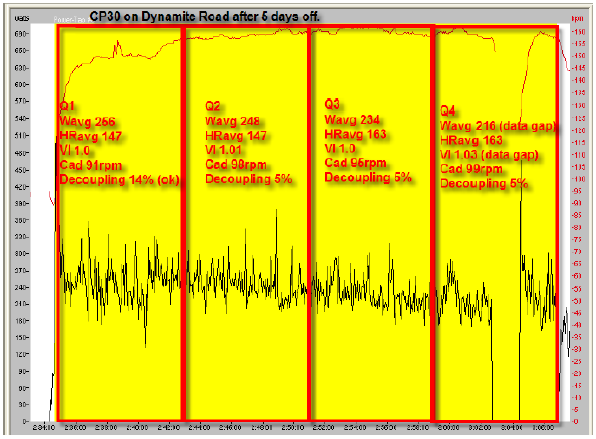

In this graphic you can see what typically happens in a long TT. While this is a CP30 test the results are what normally happen when racing a TT. Note that the power line (black) descends throughout the 30 minutes while heart rate (red) rises. (There’s a 17-second gap near the right end where the device failed leaving a data gap.)

Notice that I’ve divided the 30 minutes into four quarters with data on how each went. The average watts (“Wavg”) for each quarter clearly shows how power dropped while average heart rate (“HRavg”) rose, especially in the latter half. (The other data here is Variability Index (“VI”), cadence (“cad”), and decoupling (“dec”) which I won’t discuss now but have done in previous posts.)

I like to have the riders I coach divide the time trial course into four quarters just as I have done in the above graphic and have a strategy for each. Here is how I suggest they mentally manage each quarter of a longish time trial.

Q1. In the first they simply try to hold back. This will feel the easiest with RPE (Rating of Perceived Exertion) being the lowest of the race — and far lower than what their mind is telling them to do. This may only be a 3% reduction of power but it feels much greater. The tendency is to go out much too fast and pay the price later on. Heart rate will mean little here. RPE is everything, especially if you don’t have a power meter. If you start breathing hard here you went out much too fast.

Q2. In the second quarter, if you don’t have a power meter, heart rate and speed are watched closely. Realize that if it’s a windy day or a hilly course then speed means little. Power makes this so simple. Just ride at goal average power in quarter 2. If using a heart rate monitor and RPE stay in your goal average zone with an RPE which is only slightly harder than for the first quarter. Do not let heart rate rise above goal heart rate. Stay in tune with your technique and breathing while being careful not to get caught up in “racing” your minute man. Concentrate on your own race — not his or hers.

Q3. The third quarter is the toughest. If you will slow down, this is when it will happen. The purpose of the first half of the race is to prepare you for this section. If you controlled your effort and stayed in the moment earlier you will now be able to maintain average power, heart rate or speed here, altho it will now feel much harder. In other words, RPE is now rising rapidly even though your body is not working any harder than before. During this quarter you may well say to yourself, “I’m not doing very well. Going too slow. I’m going to get passed.” That’s normal. Expect it. Everyone will think that during this segment. Maintain focus and effort. Play “pedaling games.” Count pedal strokes as “1-2-3-1-2-3, etc”. On “1” apply more force and let up on “2-3”. That means that each leg will get a 5-stroke “rest.” Or try a 5-beat. Nearly 25 years ago in his book, Bicycle Racing, Eddie B. suggested pedaling with “only 1 leg” for a few strokes while the other “rests.” Do whatever you need to mentally get through this section of the race. It is by far the toughest even if you paced properly earlier. If you didn’t then this part is incredibly depressing. You are likely to surrender to your minute man here.

Q4. In the fourth quarter you know there are only a few agonizing minutes left. The end is mentally in sight. It’s just like the horse smelling the barn – you feel capable of increasing the RPE. Now you can race others IF you held back in quarters 1 and 2. Try to gain on someone up the road. Concentrate on that target. With a couple of minutes to go begin to increase the effort gradually. Try to pass someone. Go hard, but if you can sprint you held back too much. You should finish feeling as if nothing was left on the course.

Mental preparation is critical to time trialing. Riders have told me of their “TT tricks,” like imagining where they would be if they were on their interval course at home or “mentally” singing a song that has the right rhythm for their stroke. These may come in handy in quarter 3. When doing your time trial interval workouts (you’re doing these, aren’t you?) try doing four long intervals with each using the strategy you will employ for that quarter in the race. Don’t wait until race day to practice this.

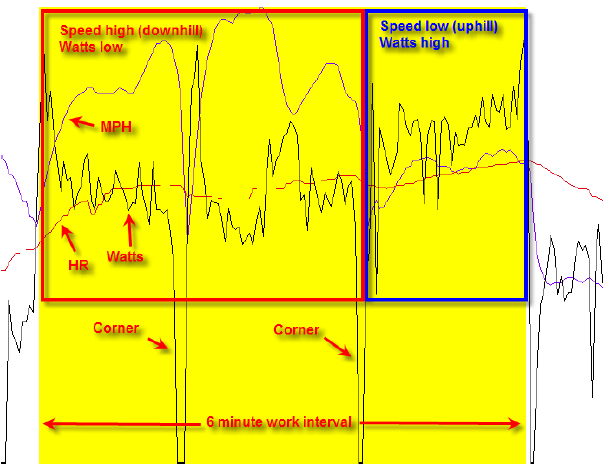

Another element of successful time trialing that must be practiced is riding the hills so as to optimize performance. On all hills, including just small rollers you hardly even notice, ride slightly harder on the up side and slightly easier on the down side. This will help you gain time while giving your legs a small break. This also needs to be rehearsed when doing TT intervals. The accompanying chart illustrates how this was done. Here you can see a single six-minute interval from a workout. The early portion of this interval was slightly downhill as you can tell because speed (“MPH”) was high. So power was allowed to drop slightly here. In the latter half of this interval speed was low because of a slight uphill so the rider increased the power. Again, this should be rehearsed when doing time trial workouts.